DEATH OF A NATION Canadian vs. American Post-Apocalyptic Visions

by Jamie Mason

Broken windows stretch to the horizon. A noxious twist of grimy smoke clutches the clouds and a stench of bodies – the piled carnage of the City’s dead, an odor to corkscrew even the heartiest stomachs – lies heavily on the street. A door opens in a darkened shop-front and a man swathed in camouflage steps into view carrying an automatic rifle. The pearl-colored light reflects in his mirrored shades and the red, white and blue of his shoulder patch provides the only flash of color in an afternoon the hue of gun-metal and sorrow. A noise. He spins, bringing the rifle to bear … and is brought up short by the sight of a young, unarmed woman with a backpack slung over one shoulder, a maple leaf sewn into its pocket flap. She grins and flashes a peace sign. 1. The journey inevitably influences the traveller. But it is equally true that the traveler defines the journey. This is never more true than in the post-apocalyptic genre. One of my favorite films is the oft-overlooked 1985 gem REVOLUTION, starring Al Pacino. When Tom Dobb, the illiterate fur trapper Pacino plays, sails into New York Harbor on the eve of the War of Independence, he sums up the chaos unfolding in the streets tersely: “New York, goin’ crazy.”

The opening scene of that film confounds every expectation by painting the launch of the American Revolution with images of unimaginable brutality and human ugliness. Mobs smash British shop-windows, tear down statues of the King and (sadly for Tom) confiscate boats for the cause. Although history has vindicated the wisdom of the American Revolution as a critical step in the advancement of human freedom, I can’t help believing that the film’s portrayal is likely accurate. Strip away the historical bunting, and America was basically a colony that revolted against its landlords. Its birth was midwifed in a blaze of gunfire and death. War is war and, no matter how noble the cause, it’s always certain to unleash a level of apocalyptic violence. Canada’s birth was more ambiguous. We came into existence two short years after the end of the American Civil War, the result of a process that began in direct response to that conflict. By the time the British North America Act was passed, Canada was a sprawl of disconnected communities, ripe for annexation by a vigorous and ambitious neighbor. Invasions had been attempted five times in two previous wars and there was no reason to expect it wouldn’t happen again. (Indeed, a few of Lincoln’s generals lobbied for it.) Independence from a war-weary Britain seemed the most prudent way to secure the national welfare. Negotiations were lengthy and complex, tangled in British legal red-tape and impeded by competing colonial claims. Sir John A. MacDonald, our first Prime Minister, rose to lead a nation that was still very much unexplored and only just beginning to understand itself. Canada very literally emerged, blinking and uncertain, from the mists of the historical wilderness into a deafening silence.

2. In our beginning lies our end. These two emergence narratives have served to shape, fundamentally, the contrasting American and Canadian visions of the post-apocalypse. I would hold that while television shows like THE WALKING DEAD and JERICHO and novels like WORLD WAR Z and THE PERSEID COLLAPSE portray a uniquely American apocalypse, Canadian equivalents such as ORYX & CRAKE, the collected stories of FRACTURED: TALES OF THE CANADIAN POST-APOCALYPSE and my own KEZZIE OF BABYLON (Permuted Press, March 2015) offer an equivalent Canadian vision unique in its own right. While there will always be an appetite for American entertainment north of the border, our American friends might be surprised to learn how our apocalyptic visions differ.

3. ENEMIES & ANTAGONISTS Every good post-apocalyptic tale needs an enemy, and in American stories that enemy is usually a group or (in the case of zombies) a faceless horde which must be attacked and defeated militarily. THE WALKING DEAD handles this trope well, providing combat engagements pitting the protagonists against legions of zombies as well as human threats like the Governor and his dystopian serfs. WALKING DEAD s/heroes pack guns and katanas and these tools are always the go-to choice when trouble comes. This is not to dismiss other points of tension in the show (exploration, parlay with bad guys, character arcs), but to highlight the uniquely weaponized nature of the American post-collapse world. In a nation where the right to own firearms is enshrined in law and whose birth occurred in a storm of violence, it is logical that its death-throes would subside to the howl of gunfire. By contrast, the “enemy” faced by the main characters of Morgan M. Page’s poignant “City Noise” (FRACTURED: TALES OF THE CANADIAN POST-APOCALYPSE) is of an entirely different order. In Morgan’s vision, Toronto smoulders in the aftermath of a nebulous event known only as “The Crash” (an end every bit as ambiguous as our nation’s founding). The protagonists, Sarah and Johnny, are both transsexuals caught in the mid-point of transition when The Crash occurs, leaving them to scavenge in a blighted city for the drugs their bodies need in order to continue their biological migration. Instead of hordes of zombies to be vaporized by gunfire, the enemies Johnny and Sarah face are the ticking time-bombs of their own medically-altered biology, caught mid-way through a complex and transformative procedure

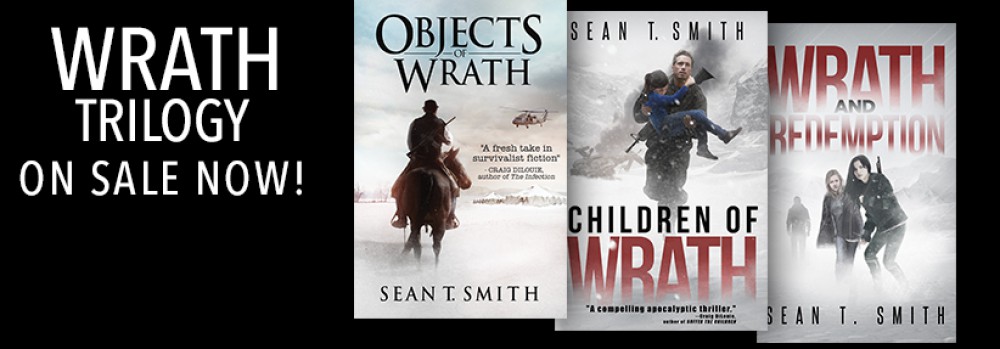

INDIVIDUAL VS. GROUP The cult of individualism is strongly rooted in the American consciousness and, for this reason, plays a titular role in any American post-apocalyptic story. The tendency for people to coalesce in a crisis is a historical given. But in American PA tales like OBJECTS OF WRATH (Permuted Press, 2014) the need for individualism sometimes leads to tragic results. One of the most poignant scenes in the novel involves a group of military first-responders flying into a remote encampment to offer aid to some backwoods survivalists. The unit’s doctor is turned away from caring for the group’s terminally-ill children because he is black. Here, hyper-individualism – the determination to survive with or without assistance from others, despite all logic – plays out in the ideology of a group existing in opposition to mainstream values of racial equality. Contrast this with the plot of my own novel, KEZZIE OF BABYLON (Permuted Press, 2015) wherein the Canadian tendency to seek accord and accommodation within groups – however dysfunctional – leads to disaster. A commune of biker outlaws, sheltered in the sanctuary of a remote grow-op in the hinterlands of Vancouver Island has, within its ranks, a deranged psychopath determined to impose her religious vision upon the group. The reluctance of the collective’s leaders to confront and disempower this person leads to murder, imposition of a form of worship that involves zombie crucifixion and (ultimately) destruction of the commune itself. Like those whose appeasement of the Quebecois nationalists resulted in the Meech Lake debacle, the reluctance of Buzz and Deacon to act allows Kezzie to take over and slaughter any who oppose her.

RELATIONSHIP TO NATURE Although environmental devastation often triggers the apocalyptic moment in American PA stories, it is rarely an ongoing threat as the plot progresses (THE DAY AFTER TOMORROW and Cormac McCarthy’s THE ROAD being the only exceptions that spring to mind). By way of final example, I contrast two short stories with the same title, one American, one Canadian. In Eric Del Carlo’s fascinating and brilliantly-rendered tale “The Herd” (OG’s Speculative Fiction, Issue #11), the Earth’s collapsing environment unleashes a series of devastating storms, driving a mass migration of human refugees ahead of them. Because I have spoken with Eric about the story’s origins, I can reveal that “The Herd” is based on his own experiences during Hurricane Katrina. Former residents of New Orleans, Eric’s family joined the stream of refugees clogging the highways just like the characters of “The Herd”. But it is what the storms cause people to do to each other as opposed to the storms themselves that form the real basis of Eric’s story. This in contrast to its Canadian counterpart. “The Herd” written by Tyler Keevil is first up in Exile Edition’s 2013 DEAD NORTH: CANADIAN ZOMBIE FICTION. In this unique twist on the zombie trope, Tyler presents us with a zombie horde migrating across the tundra, shadowed by an Inuit hunter. At play in this crisp, visually-evocative tale are all the elements of the classic Canadian wilderness survival story. It is Man against the elements as much as it is Man against … whatever. “A heaviness is in the air, a change in temperature, the wind, the look of the clouds. I know it is going to snow, and it comes in the early morning, just after the herd has set out. It arrives first, as a brief sprinkle … Then a lull, the air charged with a static crackle … Some of the deadheads stop, confused, and look up at this white confetti raining down …” – “The Herd”, Tyler Keevil, DEAD NORTH (Exile Editions, 2013) 4. And so we can see: the post-apocalyptic visions of both Canadian and American writers are informed by the human experience and social dimensions of the writers’ host countries. But it is in our origins, I think, that we find the defining characteristics of each country’s post-apocalyptic vision. We must remember that America and Canada are both nations engaged in the ongoing process of democratic evolution. Societies in both countries adapt to prevailing circumstances, learning from their mistakes, making mid-course corrections and each working to preserve the ongoing experiment that is any free society. We are unique, yes. But we influence each other enormously and are mutually fascinated by visions of the apocalypse. Americans, robust and individualistic, fight each other over possession of the wasteland while Canadians, willing to pay almost any price to remain within a group – however dysfunctional – seek to survive its ambiguous wilderness. As both nations emerge from history and grow toward self-actualization, we both imagine our own demise only to discover that we die very much the way we were born.

My friend Jamie Mason is a Canadian writer of dark fiction whose stories have appeared in On Spec, Abyss & Apex, White Cat and the Canadian Science Fiction Review. His zombie novel KEZZIE OF BABYLON was published in March of this year by Permuted Press. He lives on Vancouver Island. Learn more at www.jamiescribbles.com